Previously, The Mary Sue argued that we should be critical of ‘objectification’ by ignoring contexts of characterization and treating anime girls as no more than objects in the first place. Now they want the community to be ‘critical about cuteness’, as they vaguely denounce the ‘adult male’ viewership of moe as misogynistic, and conclude that moe is ‘alienating’ for those who want to see ‘real women’ in anime, and not the lovable and hyperreal figures modern Japanese culture is full of.

Many of its most important points rest on assumptions placed on the perception of moe, and not an evidenced understanding of Japanese culture and what moe was born from. This extends into the article’s treatment of Galbraith’s The Moe Manifesto, a plethora of different opinions on moe from industry experts. The article selects a few quotes and uses them to speak of a ‘vein of misogyny’, but divorces what it presents from an understanding of the otaku audience. To The Mary Sue it seems there is nothing to be understood about moe’s fans, when Galbraith’s scholarship demonstrates that they are one of the most diverse and fickle groups of consumers in the postmodern age.

In response to the piece, Youtuber Digibro vlogged his concerns with ‘outsider articles’. Many in response misunderstood his message, making claims about how you don’t need to be an ‘expert’ in anime to talk about it, or that the writer is more than ‘qualified’ to discuss moe. But qualification isn’t the issue; Digi’s concern is that he knows, from reading the article, that the author’s discussion of moe and its ‘problems’ is far away from what he considers moe to be. I share his complaint. The Mary Sue feels like an ‘outsider’ because they haven’t been sensitive to understanding how the ‘adult male viewers’ really view this media. This concern is corroborated by Galbraith in an essay on the lolicon phenomenon:

“There is a gap between what fans think they are doing and how regulators understand their actions. This is all too obvious when images from manga, anime and games are extracted from the specific lifeworld context of fan communities and scrutinized with regard to abstract and universal notions of child abuse. Despite the possibly criminal nature of the representations, fans do not understand highly stylized characters as “real” or sexualized representations of young characters to be “child pornography.” – P.W. Galbraith

This isn’t to say, however, that you have to be in the ‘lifeworld’ of moe to criticize it. But being into moe is a complex state of identity for many who already feel socially alienated by what lies ‘outside’ it. By supporting the pretence that you can understand their media without understanding how they view it, you end up trivializing their unique mode of viewership, and alienating them further as a result. The way moe fans want people into moe to discuss it ‘critically’ is akin to how the article’s author is desiring articles from marginalized communities; when a writer shares the identity they discuss, they tend to be more sensitive to the matter at hand, and not stomp around with generalizations, calling ‘discussion’ what amounts to no more than bulls exchanging shards of broken china.

By citing infantilization and ‘the male gaze’ as ‘problems’ we need to be aware of to ‘fix’ our community, the article has rejected the very vitality of moe and the identity of those who enjoy it. While it ends on a note of being ‘inclusive’, it never seeks to understand the lifeworld of moe viewership, and trivializes and alienates those who partake in it. In order to really understand what problems arise from moe, we need to more carefully understand how its hyperreal bishojo are consumed by otaku, and how that differs from what we’d expect at a glance.

Along with a far more representative selection of the views expressed in Galbraith’s scholarship, I hope to clarify that TMS is working towards the opposite of an ‘inclusive community’. Its article on moe demonstrates a desire to tear down moe entirely, by giving a false witness to the ‘cuteness’ moe fans love as misogynistic and problematically infantile. The real problems with moe lie with its misuse: at its heart, moe is something The Mary Sue should only be praising.

The Nature of Hyperreality

Moe is a feeling of protective love, or loving protection, towards ‘fictional characters or representations of them’ (Galbraith). One of The Mary Sue’s key issues with moe is that its mode of empathy ‘isn’t applicable to women in the real world’. It emphasizes this as part of the ‘cuteness problem’, when this is exactly what moe is engaged with to experience; a second empathy, an alternative love.

The article outlines fairly how otaku don’t conflate virtual maids with a desire for the real thing, and yet remains to treat the hyperreal vulnerability of moe as an issue, never being sensitive to the ‘reality’ moe stands in contrast to. Indeed, its hyperbolic notion that ‘the stereotype of teenage girls in the real world is closer to “incomprehensible she-demons who just want to have sex”’ portrays a strongly Eurocentric viewing of anime, and a lack of sensitivity to Japan’s social and cultural situation for both men and women.

It’s proposed that moe is an issue for relating to the ‘real women’ that otaku will encounter ‘every day’; the writer has neither a sensitivity to understand hikikomori as consumers nor how moe is a cultural separation from ‘the real’ as society would consider it. Moe anime offer a virtual space in which the viewer disconnects from reality. While some may criticize this as ‘escapism’, it’s vital to consider what many otaku are actually escaping from. And where they escape to correlates to that:

“The period of life regarded as most valuable in Japan is from middle school to high school. This is the period of adolescence, of youth, that is the most pure. The world seems to be so full of promise, you know? Everyone has hopes and dreams, which they have not yet compromised by joining the institutional culture of the salaryman society.” – Kotani Mari

Japanese feminist Kotani Mari’s words above criticize the notion that a school setting is used for ‘insta-empathy’. The aspects the article lists as causing such ‘insta-empathy’ cannot cause it alone, because, as Galbraith notes in The Moe Manifesto, “the response isn’t to the material object, sound, costume or person, but rather to the character”. It isn’t the school uniform that causes moe – it only works as a catalyst, placing the character in a time ‘that is the most pure’, a time the otaku wishes to return to themselves.

“not everyone had the best possible experience in high school. So they want to go back and experience it as it might have been… almost everyone in Japan has been to high school, and this shared set of experiences is something that we build on.” – Maeda Jun

It is true that moe empathy ‘isn’t applicable to women in the real world’, because it’s not to a ‘person’, but rather a ‘character’. But it’s preferable to many ‘adult male otaku’ because the ‘real world’ pressures them with an ‘institutional culture’ of masculine socioeconomic responsibility, which in Japan is where a real ‘vein of misogyny’ – along with a limitation of masculinity – lurks, as men are expected to become salarymen for women to see them as breadwinners:

“Clearly we are talking about those who are marginalized – Japanese men in particular, who seem to be getting weaker. After the Second World War, the value of men in Japan was determined by their productivity at work. The man who earned money was able to spend it, showing that he was a worthy mate. This then became the only way to be a man, the only way to be favorably appraised by women. (…) So those men who failed or dropped out of the system looked for love elsewhere, for example in manga and anime.” – Honda Toru

“In some ways, the image of a Japanese otaku as an obsessive, socially inept, technologically fluent nerd represents a type of manhood that is a polar opposite to that of the gregarious, socializing, breadwinning salaryman.” – Ian Condry

This also doesn’t limit moe, however, from being actualized outside of a viewer-character relationship in fiction. Recall Galbraith’s notion that “moe refers to a response to fictional characters or representations of them”. Within the scope of ‘representations’, Eiji’s considerations of what kind of ‘realism’ moe operates on are useful:

“Ōtsuka Eiji… proposes that there is an internal, enclosed reality to manga and anime. He calls this “manga/anime-like realism” (manga anime teki riarizumu), as opposed to “naturalism-like realism” (shizenshugi teki riarizumu), in which reality is determined by resemblance to the natural world. Fiction resembles fiction, or follows its own logic, and captures a sense of autonomous reality.” – P.W. Galbraith

This is what postmodern theorist Jean Baudrillard would term a ‘simulacrum’; a state where fiction does not respond to ‘the real’, and ‘the real’ is not asked to respond to the fiction, where there is no sense of a single ‘original’. As Hiroki Azuma writes:

“The discernment of value by otaku, who consume the original and the parody with equal vigor, certainly seems to move at the level of simulacra where there are no originals and no copies.”

The fiction becomes separate, a second world. However, ‘the real’ can tap into that world, and resemble fiction, as exhibited by the existence of maid cafes in Japan. Thus, if a ‘real’ girl can perform a ‘moe’ character in that environment, there is no reason to exclude or denounce the possibility that any ‘real’ girl could willingly choose to act ‘moe’ for those around her.

And why shouldn’t she be allowed to? The writer posits that she has no experience with people acting in such a fashion, and uses the fact as some kind of evidence towards a wider statement of ‘real women’ not acting this way. But I have many friends who act childish, to men and women alike, in order to create a calm atmosphere, a sense of co-operational safety – to reduce listeners down to a childlike state of interaction along with them – and, most importantly, to assert attention from people. Regardless of personal experiences, the choice to act childish shouldn’t be condemned on any grounds; we are always acting younger or older than we actually are, and transforming the characters of those around us with the level of maturity we choose to perform.

It is this transformative power of character that erases another concern of The Mary Sue; the belief that moe is framed for – for some people, defined by – the ‘male gaze’.

The Moe Gaze

At first the concern is apt; we have a simulacrum of shy, clumsy girls who appear to be in service to a commonly male viewership. But these aspects do not make the ‘male gaze’ – as coined by Laura Mulvey – as a whole, just as a ‘school setting’ and ‘cat ears’ do not make moe alone. The essential issue of the ‘male gaze’ is the cinematic reiteration and reinforcement of a patriarchal paradigm between the sexes. But layman feminism has a tendency to slap ‘the male gaze’ on any fictional weakness of women that is witnessed by men, without being critical of whether a patriarchy is actually being facilitated. So it is with The Mary Sue:

“when aiming for a moé response creators often try to generate insta-empathy through devices like cat ears, hyper-feminine costumes or a school setting, all calculated to position characters as vulnerable–relative to the adult male viewer–from the start”

The Mary Sue refuses to understand the perception of the ‘adult male viewer’ it speaks of; it doesn’t consider the clumsiness and shyness of moe girls as being born from its audience’s own social attributes. Moe feels like a safe space to so many viewers because it takes pleasure in not an establishment of a dynamic of power between the weak subject and a strong male viewer, but rather an acceptance of a weak masculinity. Rather than a strong female attracting a strong male, moe involves the weak female operating as a comfort for the weak male.

The relationship is commonly initiated via a combination of the male otaku’s heterosexuality and the desire for an acceptance of weakness. The viewer loses the social identity of their gender – that they are worth something because of how they work – almost entirely, as the feeling of moe concerns itself with insertion not into a male voyeur within the story, but the girl that moe is felt towards herself:

“More than a desire to date a cute girl or anime character, it is a desire to become her.” – Momoi Halko, voice actress (1)

The viewer turns from a sense of self-worthlessness to finding worth in someone else’s struggle; ‘protecting’ a moe girl comes not to be a restriction on her unique potential, but an enabling of that potential. There is no one ‘ideal woman’ moe girls grow into – heck, it’s not ultimately about them growing at all. It’s the love of the juxtaposition between a sense of striving for growth, and a sense of loving things the way they are. A moving stillness of imagery.

One of Mulvey’s greatest issues with the ‘male gaze’ in cinema is the passivity it instills into women while the masculine is asserted as strong. But ‘moe’ girls, despite their appearance of vulnerability, operate towards the inverse; they initiate the viewer-character relationship with their cuteness, and the viewer is the respondent to their agency. When Ito Noizi says “they don’t strategize and play games with people”, we must bear in mind that the moe culture involves the man not ‘playing games’ with them either. To exact the true feeling of moe towards a character, you have to cooperate on their level of childishness. You escape the game-playing of the adult world, that place of responsibility. Moe is a space of pure, co-operational trust.

Moreover, in Mulvey’s eyes, a ‘strong female’ uses their sexuality to dominate men. What could be more dominating than the reduction of the masculine down from any chance of a patriarchal podium – down to a feminized, co-operational state? CGDCT shows often are exclusively led by girls, presenting a sense of the ‘high school’ otaku escape to as being run by their autonomy. Thus, in Mulvey’s feminism, the projected weakness and vulnerability of a moe girl actualizes their strength, as they refuse a ‘male gaze’ upon that violability and instead use such aspects to tear down the distance between viewer and character genders entirely, not only on a personal level, but for the depiction of high school life for otaku at large.

It feels to me that the moe girl owns the high school in anime, and the male is merely to be ready to join them in whatever struggle they are leading. It’s a far cry from the ‘cheerleaders’ of Hollywood who are only there to support the man’s ambitions. Those watching New Game! support Aoba’s passion. Watching Hibike!, we support the girls as they support each other. And in return, from our feeling of supporting them, we are rewarded with a sense of them being there for us, as we break down binary barriers of gender and age and come to a mutual, virtual place of love and comfort.

It’s disappointing that the article begins to praise moe’s progress for LGBT viewers and subjects, but fails to recognize the greatest factor into this being the case. Moe is a departure from the misogyny of a society where men are expected to be the breadwinners, and women to follow their lead. In forgoing that responsibility, male otaku embrace a rejection of their masculine distinction from the feminine. They enjoy a process of feminization as they cooperate with shy figures that answer to their own shyness. They participate in a breaking-down of gender constructs at large. Momoi Halko and Mark McLelland have aptly considered moe as a ‘third gender’; though it is a feeling catalysed by standard distinctions of gender – heterosexual or homosexual – and age – adult and child – it places the viewer in a position beyond social constructs of gender and maturity.

“If being a man ceases to promise power, potency and pleasure, it is no longer the privileged subject position. Akagi explains that lolicon is a form of self-expression for those oppressed by the principles of masculine competitive society. Lolicon is a rejection of the need to establish oneself as masculine and an identification with the “kindness and love” of the shōjo. This interpretation reverses the standard understanding of lolicon as an expression of masculinity to one of femininity.” – P.W. Galbraith

“So you have women becoming male characters and men becoming female characters. That’s the flexibility at the heart of moe.” – Momoi Halko

Empowering Protection

Another issue that arises is the infantilization of women that moe portrays. What we have already covered renders The Mary Sue’s issue below moot:

“even in subtler shows isn’t that still the core idea? That these girls are simple souls with pure dreams and warm hearts who just need to be protected so they can grow into the ideal woman?”

We know that moe girls are so often teenage because their audience wants to return to state of adolescence themselves, to ‘become’ these girls. The infantile is so commonly used for moe because it elevates the sense of weakness for the character, a sense that exists not for the viewer, child or adult, to exert domination over. No: they share in it. Just as strong female characters promote men and women alike to share in the strength of humanity, moe girls promote confidence in clumsiness. That it’s okay to be shy and childish, as many of moe’s ‘adult male viewers’ are.

This feeds into one reason why moe often works so well for comedy: a theory called ‘benign violation’. Comedy often occurs when there is some sense of ‘violation’ – some rule being broken, from as little as work-play to something physical or social between characters – that is backgrounded in an expression of being benign, of only meaning well. Tickling is a prime example of this in effect. The clumsiness of moe girls, who violate the social tradition of needing to be ‘mature’ in high school, along with their benign feelings towards each other, and the viewer’s benign feelings towards them, creates a pleasurable space that the viewer can easily identify and sink into, a space ripe for comedy and celebrating the pleasantness of life.

But often moe is deeper and more challenging to its viewers. In Love, Chuunibyou and Other Delusions, Rikka is perhaps the perfect example of an ‘infantilized’ girl, but this correlates to the totality of her delusional character, stuck in boyish fantasies she adapted from seeing our protagonist perform them back when he was in her phase. The anime is partly about destroying the assumption that there is an ‘adult’ who can exert authority over this sort of child and make a worthwhile relationship. The Dark Flame Master realises that he must cooperate with her, and perform his own ‘inner child’, in order to help her mature.

I felt a great sense of endearing for Rikka as I watched Chuunibyou, but it wasn’t a sense of power. It was me coming down to her level, understanding her world, and working emotionally within it. There’s an incredible scene where the mundanity of tidying her room becomes a heart-wrenching task, because she doesn’t know what bits of her ‘junk’ to throw away. It’s a similar emotional action that I felt in the Toy Story movies – Pixar wanted parents to understand better a child’s fascination with their toys. Toy Story may not be ‘moe’, but Chuunibyou communicates a similar message through its moe, of needing to understand childish dreams and ‘delusions’ from the inside.

This process of coming down to the level of a child, to understand them, is presented fantastically in Amaama to Inazuma, a show The Mary Sue takes a screencap from. Opinions vary on how much of a feeling of ‘moe’ the viewer is designed to have towards the show’s characters. But within the show itself, we can notice a vital aspect of ‘moe’ actualized between the characters; Tsumugi’s actions often lead to Kotori becoming more childlike herself, as she non-sexually revels in Tsumugi’s carefree spirit and at times has directly paralleled her in expression, practically becoming her just as viewers of moe ‘become’ the moe girl themselves.

Episode 7 of Amaama to Inazuma also highlights two ways of approaching something Galbraith noted of moe – that it’s a protective feeling that ‘would do any father proud’. In the episode, Tsumugi leaves home on her own, and is met by a variety of ‘protective’ responses to her autonomy. Two high school students help her cross the road, protecting her from the danger of traffic while ensuring her autonomy – they don’t, however, consider why she is alone. Tsumugi’s father, on the other hand, yells at her for leaving home, concerned only with the danger of her leaving home and denying her right to such a autonomy as a child.

Between these two extremes, Kotori establishes what I believe the ‘protective’ instinct of moe to be; an acceptance of a desire for independence, with a safeguarding from anything that could disrupt that freedom. Moe is not the cage a father must put around their young child, because moe girls are usually high school students. But neither is it the abandon of care in totality. Moe is a kind of confidence; the assurance of the freedom of the girl, and the protection of that freedom and however the girl wants to pursue it. This is not what Tsumugi can be allowed, since she is literally a child, but it is what a childlike adult is asking for from those around them; confidence in their carefree nature.

Simiarly, for fans of ERASED, Satoru’s feelings towards Kayo should represent the real moe; the infantilizing of the self and the protection of the infant that affected the self from those that would take advantage of their vulnerability. Vitally, Satoru does not take advantage of Kayo either; he does not use the ‘virtual’ connection of being an adult in his child’s self to create a real relationship with her. He has an enriching time with her in their co-operational vulnerability, protecting her from the killer that sought to deny her a future, and he does not get in the way of her future either. He is satisfied to leave her free to grow up how she wants to. Not into his ‘ideal’ mature woman. Once she is safe, he transfers his attention onto the next person who is not, and Kayo continues her life how she independently chooses. Similar is the way we may jump from waifu to waifu; one season Uraraka, the next season Rem.

For some, however, satisfaction from being ‘protective’ towards a moe girl may be so great that they want to create further opportunities for that sensation. Fan art, fanfiction, cosplay, character songs – many extensions to stories exist partly to give those who cling to one singularity of moe more opportunities to see the figure further their own individual struggle and lifestyle. We must be careful, however, in our fan art and other appreciations, that we don’t divorce the character from their moe identity. As mentioned before, many erotic fan-creations surrounding moe girls rob them of being moe completely.

To abuse the infantile imagery of moe girls and not become a child with them is to engage in a false moe, which most ‘moe’ hentai is guilty of. Pornographic ‘moe girls’ are often envisioned as not cooperating with male figures in mutual childishness, as the feeling of moe, though perhaps instigated at first, is replaced with satisfaction of refusing that model and taking advantage of the girl’s state to exert power and authority over them. Consumers insert into the male rather than the female, and the female reaches for a masculine depiction of maturity, which destroys the sense of ‘moe’ entirely.

But this does not mean moe cannot be felt towards girls in sexual situations. The ‘lolicon’ obsession of some otaku, which must not be conflated with paedophilia (2), and is not synonymous with moe either, as much as it taps into the same drive of childish care, is understood well by Itō Gō on the issue of a matter as volatile and historically misogynistic as fictional rape:

“Readers do not need to emphasize with the rapist, because they are projecting themselves on the girls who are in horrible situations. It is an abstract desire and does not necessarily connect to real desires. This is something I was told by a lolicon artist, but he said that he is the girl who is raped in his manga. In that he has been raped by society, or by the world. He is in a position of weakness.” – Itō Gō

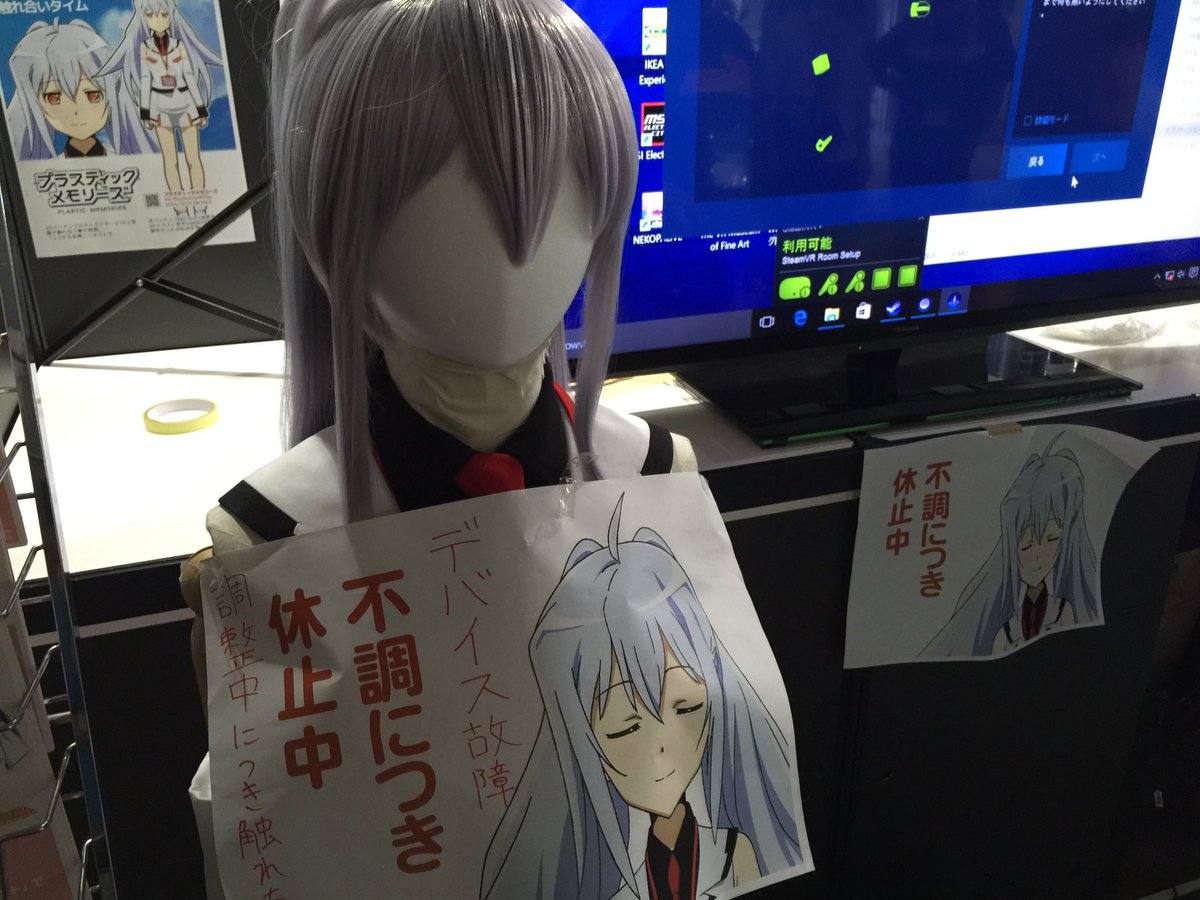

Regarding a recent VR exhibit, featuring a virtual recreation of Plastic Memories’ Isla complete with a doll for physical contact, many onlookers have immediately assumed that the experience is designed to cater to fantasies we have every right to call out as problematic; the indulgence in the inertness of the girl, the literal stillness of the doll, and the sense of there being no social or moral barriers between one’s self and the static simulacrum-satisfying person. A number of participants couldn’t resist groping the doll’s breasts, eager for the virtual response.

However, those running the exhibit have ended up banning people from interacting with the doll in this way. The project was intended to be a family-friendly interaction with a virtual girl, not an opportunity for shut-ins to get some action. Taking advantage of the girl’s vulnerability is the opposite of what the exhibit was made for, and ultimately the opposite of what ‘moe’ is all about – being, as a viewer, in a ‘position of weakness’ with the character, and not placing a woman into infantilized weakness so that you can assert authority over her.

This leads us to a major problem, and what The Mary Sue ought to have focused upon: just as we can rob a moe girl of moe by making her conform to ‘real’ sexual activity, so can we also rob ‘real’ people of their identity by forcing ideals of moe upon them.

How the Alienated Can Alienate

One of the greatest problems of feeling alienated by a society is that, returning to that society, you can end up trying to mould ‘reality’ into fitting the fantasy you escaped to. There’s a massive difference between girls choosing to tap into the simulacrum of moe – as many cosplayers do – and a girl having it projected upon her as a set of social demands. The more we have of the latter, the harder it is for the former to not be met with skepticism and conflation with the latter. We come now not to be ‘critical about cuteness’, but concerned over how that cuteness is appropriated and acted upon by its viewers.

I was surprised that, out of all the shows this season exploring and presenting moe, that the article never touched upon Kono Bijutsubu ni wa Mondai ga Aru!. Many respondents to the article have already criticized the screencap from Love Live!, with the franchise being one of the most ‘inclusive’ in anime history. Meanwhile, many of the ‘excluding’ problems of moe the article talks around can be evidenced well by examining the interactions between the characters of a show that’s all about a ‘real’ girl confronted with the inability to be noticed by a guy who’s only care is for 2D girls.

The ending of Kono B’s first episode was thought-provoking. After a few skits introducing the central conflict between a girl’s unrequited love and a boy’s attachment to the waifus he draws, Mizuki ends up gaining an emotional response from Subaru; a response we can quickly understand as moe. But while this rests in Mizuki’s heart, we see Subaru moving on from it quickly, and not having it build at all into a greater sense of a relationship with Mizuki. His rigidness is comedic, but exemplifies a cause for concern.

Mizuki elicits an emotional reaction from Subaru not because he understands any depth of her personality being displayed, but because her actions perform in correspondence to a set of interchangeable traits. Though she is a ‘3D girl’, she becomes objectified into two-dimensionality, reduced to her expressions. Subaru also dominates the setting of the show, with his art in coherence with the aesthetic of the characters itself, to the point where Mizuki’s artwork feels out of place.

But perhaps Mizukiis no better; her world of romance is just as flat. Part of the comedy of Kono B is that both Subaru nor Mizuki are stifled by a system of tropes they only live to fulfil. Subaru must have his waifus looking right, and Mizuki only wants romantic clichés – the indirect kiss, being held like a princess, and so on. Both characters are institutionalized into a lifeworld that hinder their ability to connect with each other; both reduce each other down to actions, to parts. While the show is lighthearted and offers comedic criticism on this issue, it’s also something we should be wary of at large.

This has everything to do with the taking advantage of flatness, the situation wherein the viewer engages not with the depth of a human, but upon instinct of action in an animalistic and purely instinctive fashion. The sad moe girl is makes us sad. The violated moe girl makes us laugh as the pervert gets a facefull of her striped panties. Unless the anime and its characters perpetuate some commentary or context upon such an event, these aspects are not read in coherence with the story as a singular narrative; they are moments processed into a nonnarrative of the desire for all such scenes. Within them the character becomes a noncharacter.

This is permissible if the viewer can appreciate how to stay in a simulacrum; but when such things permeate the ‘real world’, we can start treating real people as nonpeople. We can start living out the flaws of a shut-in like Re:Zero’s Subaru.

Enough has been said of Re:Zero to render obvious Subaru’s central character flaw – his ‘pride’ concerning a refusal to see this ‘real’ fantasy world as anything other than his simulacrum of shut-in experiences with games that had similar worlds. But rather than satisfy his sense of entitlement, as so many Isekai narrative do for their protagonists, the world reveals his lack of social skills, and Subaru eventually accepts that he must start ‘from zero’, having lived no ‘real’ life prior to arriving to this world. Though the world of Re:Zero has its characters look and act ‘moe’ for Subaru, his greatest development as a character has been a realization of the people behind those characters: that the Emilia in his head is not something the Emilia in reality has to adhere to.

Fortunately, the women Subaru initially flattens, or tries to flatten, are in positions of incredible power and autonomy, relative to him. This dynamic helps him make progress away from being locked in his ideals and projecting them onto other people; his delusions are eventually penetrated because of the strong characters he’s confronted with when his fantasies don’t meet reality. This speaks of how strong women in real life – sites like The Mary Sue – can be doing great work in being critical of the anime community and how people project flatness onto rounded, real people in order to try to control them, under a pretense of ‘moe’ that never actualizes what moe is really about. If only The Mary Sue had sensitively understood moe, and separated its noble purpose from its misappropriation, I would have no issues to raise with its approach.

Anime that use moe as purely a comfort zone are more in danger of encouraging a perspective different to moe; though Digibro exclaims that he and his friends would never want a girlfriend to act like a moe girl, and though otaku are claimed to be heavily discerning of the difference between reality and fiction, at times the fictional simulacrum of moe is forced onto ‘real women’. At those times, we have misappropriated moe for a selfish end. We need to reject such practices as Re:Zero’s world rejects Subaru’s sense of entitlement – but we can only do so, properly, if we reject it as not being true to a sense of moe at all. We should not be moulding ‘real’ women into moe, just as The Mary Sue shouldn’t be forcing an acceptance of its view of ‘real’ women onto otaku who have felt alienated by the demands of Japan’s ‘real’ society. We should be inclusive of escapism, as long as it remains an escape, and isn’t used in a reductive return to the real.

Conclusion

Moe can be a window into lowering one’s sense of pride and entitlement, and coming to understand the person behind the character that performs via a simulacrum of cutesy stimuli. Yet, we can make a case for moe offering the potential for its subjects to be misused. The divorcing and flattening of ‘moe’ characters out of the narratives and into pornographic situations is the most common example of a contagion I’m alienated by myself. It’s not ‘moe’ that alienates, but the fear of it being misused. But we can’t let moe’s misuse lead to the denouncement of the whole of something that has such a praiseworthy purpose. We need to focus our criticism of moe upon those who distort it, and take advantage of it, and not confuse that misappropriation with the heart of moe itself.

If someone is into moe but can’t empathize with ‘real’ women too, they have something they can choose to work on; the more insecure may never make progress, however, and moe remains a valid ‘safe space’ for them to reside in. But if being into moe makes us force girls to behave only in the ‘virtual’ ways we can relate to, we have every right to be called ‘alienating’ as fans. It’s not the moe itself that has alienated, but our inability to appreciate anything other than it, and our desire to operate in a society while refusing to accept the way it works and forcing our preferred culture onto it. The trouble is that The Mary Sue has done exactly this with moe; it has criticized ‘virtual’ empathy for not being useful in the eyes of the writer. If we really want an ‘inclusive’ community, we need an acceptance of both a virtual world of empathy, and a real one. We need to appreciate how the two can communicate with each other, and criticize anyone who uses one to try to limit the other.

We need to be discerning, and not generalizing. With all its vague definitions and assertions and criticisms of moe, The Mary Sue has only taken a backwards step for the community. To move forward with moe, we need to understand that it is, at its heart, a wonderful postmodern phenomenon that often feels irradiated by the misappropriation of its assets. We should not trivialize moe and claim that it in general ‘alienates’ us, because we then come to further marginalize a subculture that grew to love moe from their marginalization; we begin to operate through what Galbraith comes to term as ‘moephobia’, at the end of his essay on lolicon culture, in refusing to understand an audience before we criticize them.

But we cannot turn a blind eye to the false moe, the warped moe, that is marginalizing ‘real women’ and all senses of a person behind the cutesy character. We should be criticizing people like Subaru, reducing those they interact with into flattened demands to conform to a simulacrum. We should be celebrating those that enjoy and use moe as a platform for furthering the representation of the weak and the shy. To build a more inclusive community around moe, we should be celebrating moe, and being critical not of the feeling as having some kind of fault, but of those who depart from the feeling for their own selfish ends. Surely we can frame a moe girl to cater to ‘the male gaze’. But at that point she stops being a moe girl, and we stop being part of the moe community altogether.

(1) Galbraith notes of her – “There was a time when she wanted to wash her hands of the whole thing, but she now considers moe fans as a misunderstood subculture of men struggling with and against gender norms.”

(2) If you feel like moe/lolicon and paedophilia should be conflated, please read Galbraith’s essay on the subject before building thoughts on such an assertion.

If you like these semi-academic rambling on anime, please consider supporting me via Patreon, so I can fund access to more research and resources and put that back into my blogging!

Thank you for the comprehensive and incredibly insightful analysis of moe in a social, psychological, consumer and entrainment context. This was an illuminating read, and I appreciate the level of detail, research and consideration that obviously went into it, especially as my own blog attempts to explore anime from a critical and academic standpoint. You’re an inspiration to us all.

I also admire the unbiased stance you adopt throughout, making it perhaps the best piece to follow the Mary Sue’s now infamous trivialisation of moe. My brain is firing on all cylinders, as you’ve given me so much to mull over, and I can feel my own perceptions of the issues raised shifting. I’m bookmarking this article as I know it’s one I’ll want to revisit again in future.

It’s these kinds of critical insights that makes ani-blogging such a vibrant and interesting endeavour. My only complaint would be to perhaps consider using multiple pages as the use of pages allows for digestible chunks, especially to fit around work and other commitments.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for all the kind words! It was hard to strike a balance between keeping a considerate tone towards all the research, and delivering my honest anger at how sites like TMS are marginalizing those into moe.

I think I certainly will start splitting these articles up across more than one page (two might do); would generate more pageviews as well. ^^

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey. I’m from the MAL thread that you tweeted about regarding the user who linked the article saying “DAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAMMMMMMMMMNNNNNN.” I briefly considered also linking your article and just saying “THE MOE OF THE REAL” but decided to actually write you a serious response since I ended up typing up a few words in that thread and feel it’d be irresponsible for the sake of “anime discourse” to not give you some of my food for thought. I wrote these already in the thread but assuming you aren’t going to join our happy little community, here’s a few things I wrote down, expanded/cut for the sake of being less discursive:

Overall, I think the article has some nice points. I thought what is most interesting is the idea that moe is not necessarily directed for the male gaze but rather involves a sort of mutual “weakness” and cooperation as to strip the viewer (if he is male) of his masculinity in order to embrace and feel comfortable with accepting weakness, clumsiness, social awkwardness, etc. The idea that it’s a form of escapism to live in an enclosed reality separated from the pressures and stereotypes of male masculinity/Japanese corporatism is also a noteworthy point, but I think there might be some more complicated socioeconomic issues that are not being considered. One of my big issues with most articles that argue that moe is a specifically Japanese/cultural phenomenon is not that they identify it as such, because that in itself is correct, but rather I take issue that they often conflate the issues of hikikomori or otaku culture as larger than they might actually be. I would argue your piece is relatively free from this but at times comes close to implicitly arguing that hikikomori is much more prevalent than it actually is.

As to the original point of the “moe gaze,” I’m not sure if I actually buy that argument, though again, I find it a sort of attractive point that I hadn’t really thought too closely about. This is purely anecdotal (as unfortunately most of these arguments will likely be), but I don’t feel that there’s any mutual cooperation between me and moe characters like Mugi from K-On, but rather just the usual sort of empathy towards a particular type of cuteness and personality. I will admit that I love K-On precisely because it renders a sort of nostalgia for high school, though.

In a way, I think a lot of these arguments are non-unique to the sort of empathy with the “hero of a thousand faces” archetype. Obviously there are major and distinct differences, but I can’t help but wonder whether or not the article comes too close to building a too idealistic theoretical framework for how we should identify “true” moe that it loses sight of a much more simpler idea: that moe exists precisely because there is something attractive (non-sexual) and endearing about characters that have these sort of clumsy and bubbly nuances.

With all that being said, I do appreciate this kind of optimistic/idealistic conception of moe, even if I think the reasoning itself is sort of a (haha) enclosed realism that really only exists from a truly insider perspective. I grant that the outsider article in question really misses the point, but I wouldn’t go so far as to discount some of their issues, as you precisely bring up numerous accounts of “perverted” moe which are precisely the problems that it is talking about.

Finally, as someone who’s read and studied theory himself, I just don’t like the line of argument that addresses moe as its own separate reality using Baudrillard’s argument of a simulacrum. I think the piece attributes Baudrillard’s conception of the “simulacrum” with moe without understanding that Baudrillard’s entire spiel about simulacrums are they are indistinguishable from reality. The argument that the viewers live within this self-contained reality is legitimate insofar as it doesn’t make the point that the viewer is capable of separating him/herself from it, because the whole point of simulacrum is we can’t distinguish what’s real and what’s fake.

And of course Baudrillard’s topic of simulacra is precisely that they precede reality, that there is a sort of phenomenon where the map becomes the territory, the memoir becomes the true memory, the cinematic becomes the landscape, the camera shot from the real itself. I think this gets addressed but I’m not sure I’m that comfortable with the argument implicitly making the case that the vast majority of moe fans do not have difficulty divorcing their conceptions of moe from reality. I think there needs to be more argumentation there to really make that implicit underlying argument a (haha) reality.

Anyway, all that being said, I’ve never written a response before, so all I can say is I feel your article was pretty good and had a lot of good talking points. I read some of your other stuff this morning, so if I get around to it, maybe I’ll write my thoughts there as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey, thanks for coming by!

On this issue of how ‘large’ moe and hikikomori issues are, I think the words of Eiji are very useful:

“Moé is something you feel when looking at a character. It existed in the novels of the Meiji period (1868–1912), which was a time of modernization in Japan. To regard moé as something postmodern [see Azuma Hiroki, page 170] is mistaken. Those who do so simply want to present their feelings toward fictional girls as unique and special. And popular and academic media encourage this. We have a situation now where educated anime fans are styling themselves as cultural theorists, and then you have Americans and Europeans responding to all of this, thinking that Japan possesses something special in its moé culture.”

While moe certainly found otaku culture as a singularity, it certainly does have a wider scope. I thought about touching on this a bit more, though I think I want to spend longer looking for the best non-Japanese, non-postmodern examples.

As to there being a simpler idea to it all, I fear that it’s such a simplifcation that causes people to, say, conflate moe with paedophilia. As moe is a feeling, I think it has to be defined in terms of both the state of the ‘feeler’ and the state of what they feel it towards. If we don’t do that, it’s easy as an ‘outsider’ to assume ‘this is moe’ for something that isn’t instilling moe in any normative otaku viewer.

Your thoughts on simulacra have given me a lot to think about. I didn’t gather that simulacra involve a complete breaking down of reality and fiction; more the ability to see fiction as a second reality, a braking down of barriers in that sense, and not a total confusion of the self and perception of all things. I think we can have multiple simulacra that we can go between; the brand-image media-saturated marketplace of personalities many live in and speak through is one, and anime’s culture operates in another. It’s certainly a can of worms that needs to be explored in much, much more depth; perhaps my stance for now, along with Eiji, is that while moe isn’t exclusively postmodern, it has found a commercialized execution in a simulacrum. While we shouldn’t lose sight of its scope outside that simulacrum, neither should we ignore how many people certainly have a comfortable construct, around and regarding moe, that functions as a fiction treated as another reality – which many are capable of distinguishing from ‘the’ reality, but nonetheless vie for their entertainment to form an enclosure of content and communication that doesn’t speak or answer back to the present real.

Thanks for getting a bit of traffic my way, and again for writing such a thoughtful response.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Contrary to what Eiji says, moe is unique to Japan. It isn’t found in Western media, and even in and around Western anime communities it is routinely denounced, demonized and misunderstood. Having feelings towards a character in a regular novel is not moe, because it involves imagined real people rather than manga and anime-style fantasy characters. I think Eiji was just misunderstanding what moe is.

LikeLike

I guess the first thing which catches my attention on the TMS article (and how several people talk about moe) is how it always seems to refer to “moe girls”. There are several male anime characters I’ve come across that do give me this reaction of “so moe” or something along those lines, the same way several female ones do as well. This does tie in with your thoughts on moe fans being alienated. Find it kinda funny (and ironic maybe) that despite being more attracted to men than women, I still feel alienated when people dismiss moe as misogynistic. This article doesn’t give me the same feeling, despite it, well, largely focusing on moe girls, because I guess that’s part of the “moe” you tap into here.

Hmm, I have a lot of other thoughts, but my mind’s a bit of a mess right now and I need to read Galbraith’s essays. Hope we could talk about it then. (And I hope I don’t forget or get too lazy to do so, haha.) (Apologies too, if you see this comment pop up more than once. WiFi probs.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Moe doesn’t mean wanting to protect a character, it just means having a feeling of love or infatuation towards a character. Wanting to protect a character is just one possible manifestation of that feeling. Moe also doesn’t mean a certain kind of character, and there in fact does not and cannot exist such a thing as a moe character, as moe is just a response the viewer may or may not have towards some character for some reason (calling a character a moe character implies that being moe is an intrinsic part of the character independent of the observer). There are always different kinds of characters in so-called moe anime/games, not just clumsy, shy and childish ones. And of course the anime/game doesn’t have to be a so-called moe one in order for a character to cause a moe response, e.g. Saber’s popularity is an example of moe. I like boyish characters the most, and they are the least likely to be in any particular need of “protection” (e.g. Nori in Hidamari Sketch, Rize in Gochuumon, Yui in Yuru Yuri, Hajime in New Game, Makoto in iDOLM@STER, Yukari in Girls und Panzer).

I see the term “infantilization” and its variants being dropped a lot, but if you infantilize a character or like infantilized characters that’s just your personal moe, not an intrinsic part of it. And judging by what series and characters have been popular, infantilization doesn’t even seem to be that prominent. And what does it even mean? I assume it means characters like Yui from K-On, but slice of life shows like K-On (which Haruhi outsold) have an oversized presence in the Western imagination, with many people thinking there are tens of them made every season when the real figure is less than five, sometimes zero. There are a lot of popular shows besides those. A recent NewType character popularity poll had characters like Rem, Mumei, Saber and Senjougahara in the top 10. Of Love Live Sunshine’s cast, You seems to be the most popular overall, and she has a boyish personality. She is more popular than Ruby, the most child-like character. Nico and Maki were some of the most popular in the original, rather than the timid Hanayo.

“We must be careful, however, in our fan art and other appreciations, that we don’t divorce the character from their moe identity. As mentioned before, many erotic fan-creations surrounding moe girls rob them of being moe completely. To abuse the infantile imagery of moe girls and not become a child with them is to engage in a false moe, which most ‘moe’ hentai is guilty of. Pornographic ‘moe girls’ are often envisioned as not cooperating with male figures in mutual childishness, as the feeling of moe, though perhaps instigated at first, is replaced with satisfaction of refusing that model and taking advantage of the girl’s state to exert power and authority over them. Consumers insert into the male rather than the female, and the female reaches for a masculine depiction of maturity, which destroys the sense of ‘moe’ entirely.”

Who is this “we” you are talking about? Japanese fans produce erotic and pornographic works based on “moe characters” on an industrial scale, while Western fans are irrelevant as far as fan works go. I think Tamaki Saitou had some complicated theory for why this isn’t a problem–or maybe it was Hiroki Azuma–but you could think of it as being equivalent to having sexual fantasies of someone you’re in love with, or having sex with someone you’re in a relationship with. Pornographic doujinshi also doesn’t feature just male-on-female sex, but also yuri and the female character being in a dominant position.

While your intentions are good, you are trying to put moe into a box of your own design (Digibro also did a little too much of speaking on behalf of other people). Moe is a framework or a sandbox, not a specific way of feeling towards specific kinds of characters in specific kinds of shows.

As for “forcing the simulacrum of moe onto real women,” if you are for example into intelligent characters who wear glasses, there is hardly anything wrong with having that preference in real life too. Most of the expectations you could develop towards real women based on anime characters aren’t even unreasonable (and developing such expectations doesn’t mean not knowing the difference between 2D and 3D). It’s also not the case that moe is purely fantasy and escapism and has nothing to do with the real world; it isn’t some kind of coincidence that most moe fans are the losers of the sexual marketplace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is no sexual marketplace.

LikeLike

Have you discussed this with the author of the original TMS article? She seems to be willing to engage in reasonable discourse and has even done so with the authors of the Backlogger’s blog. I think it is a conversation worth having, since both parties are willing to have it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We don’t get along, unfortunately, and she doesn’t consider this article a worthwhile contribution to the discussion. She generally just looks for ways to make me look bad, rather than considering anything I say or write seriously.

She also mocks the idea of moephobia, which also helps clarify the divide. I find that disgusting.

LikeLike

I’m unfamiliar with the past discussions you’ve had so I won’t comment on your impressions of each other.

It’s just regrettable that the door is closed on reasonable discussion here; these are two people who can articulate their opinions clearly and whose debates can help readers learn more about literary/social discourse as they relate to Japanese ACG culture.

LikeLike

its actually not regrettable at all. Cook is very unintelligent and has not critically thought about subject. its a waste of jeko’s time to discuss the matter further with person with such a baseless opinion.

LikeLike

Jeez ok that’s a strong opinion. Gonna just back away slowly and form my own my opinion…

LikeLiked by 1 person

her position is rather weak and thoroughly refuted in this article. your question is like asking martin luthor king if he sat down with George Wallace to really understand why the blacks should be subject to jim crow Laws so he can here both sides.

LikeLike